Oxford Picture Dictionary Author, Jayme Adelson-Goldstein, shares tips for laying the foundation of college and career readiness skills in beginning level adult instruction.

Oxford Picture Dictionary Author, Jayme Adelson-Goldstein, shares tips for laying the foundation of college and career readiness skills in beginning level adult instruction.

The Relevance of Rigor

“I think the next century will be the century of complexity.”

Stephen Hawking, January 23, 2000.

Stephen certainly called it. Coping with complexity is integral to our success as learners, workers, parents, caregivers, engaged citizens, and community members. If the tasks, texts, and technology we navigate in the 21st century can be challenging and even maddening for the fluent English speaker, imagine the situation of the adult English learner! Given the limited amount of time most adult learners have for language learning and the time needed to learn English, it makes sense to help learners develop strategies they need to tackle complexity right from the start. With this in mind, U.S. instructors are looking at ways to introduce their adult beginners to:

– reading tactics and foundational vocabulary they’ll need to navigate training materials, websites, textbooks, their children’s school documents, etc.

– listening strategies to help them “get the message” whether it’s delivered from a lectern or at a staff meeting

– a professional (or academic) register that supports discourse in any context

– writing frames to insure learners can convey their thoughts in a variety of formats.

In my work with teachers across the U.S., I’ve experienced an understandable pushback when I speak about introducing text complexity and language strategies in beginning-level classrooms. There are concerns that lessons won’t match the needs of learners at this level, some of whom have little or no prior education, or whose goals do not include career training or college courses. It’s not difficult to imagine why some would say that rigorous instruction is not appropriate until the high-intermediate level or later. It’s absolutely true that, as our beginning learners engage with more rigorous instruction, they’re likely to struggle —but it’s a good struggle. (Dweck, 2007) In fact, mind, brain and education (MBE) research has shown that our brains learn more when we make mistakes. (Moser, et.al., 2011) If we provide the good struggle (sans extreme frustration) within a safe and supportive environment, learners know they have permission to risk, fail, and try again. Safe and supportive means scaffolding instruction: breaking a task down step?by?step, demonstrating learning strategies, providing practice with models, using sentence frames, posting word lists, supplying reference materials, etc.

The three examples below, show how, with scaffolds in place, learners with limited language proficiency can tackle complexity and enjoy the process.

1. Pictures with a Purpose

Visuals can serve as the basis for rigorous learning tasks that simultaneously support and enhance learners’ comprehension. Learners can focus on how best to express the information they see and already understand. Through the teacher’s text-dependent questions, learners can then dive deeper into the visual to make inferences, explore points of view within the picture and look at features in the image that give additional clues to meaning. In this way, the images serve as an “on ramp” to navigating text complexity.

Sample questions a teacher might ask:

Sample questions a teacher might ask:

- Is this a restaurant? (Y/N)

- This is Ben Lu’s home. Point to Ben. (nonverbal response)

- Is the food from a restaurant or Ben’s kitchen? (Why do you say that?)

- What type of event is this? How do you know?

- What do you see in the picture?

- What does the woman in red say to the woman in pink? Who is she? How do you know? What is the woman in pink thinking?

- What are the children doing? Which children are misbehaving? Explain. Etc.

2. Charts that Challenge

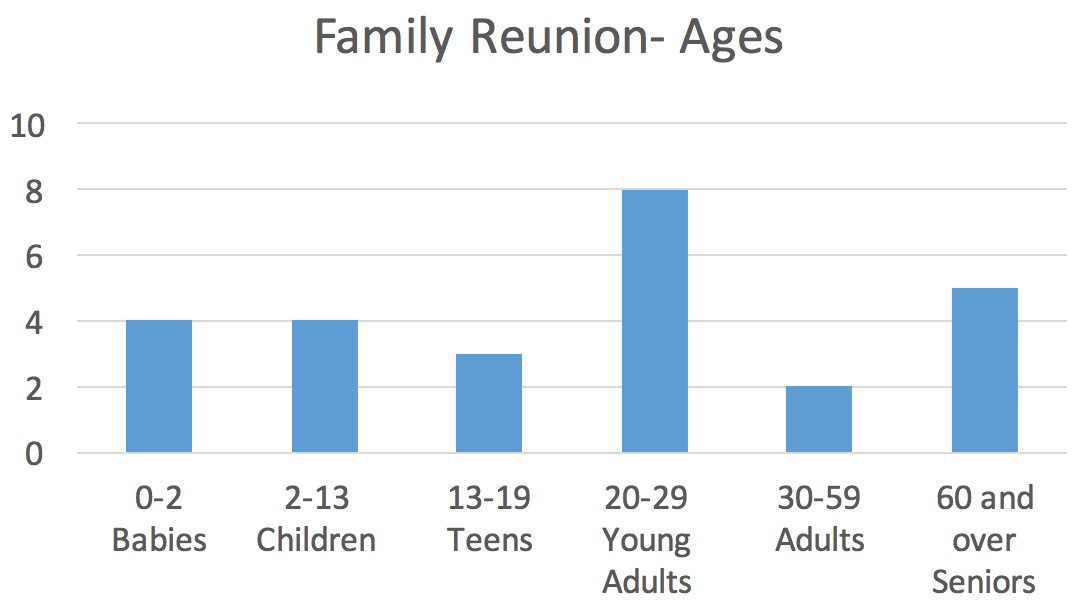

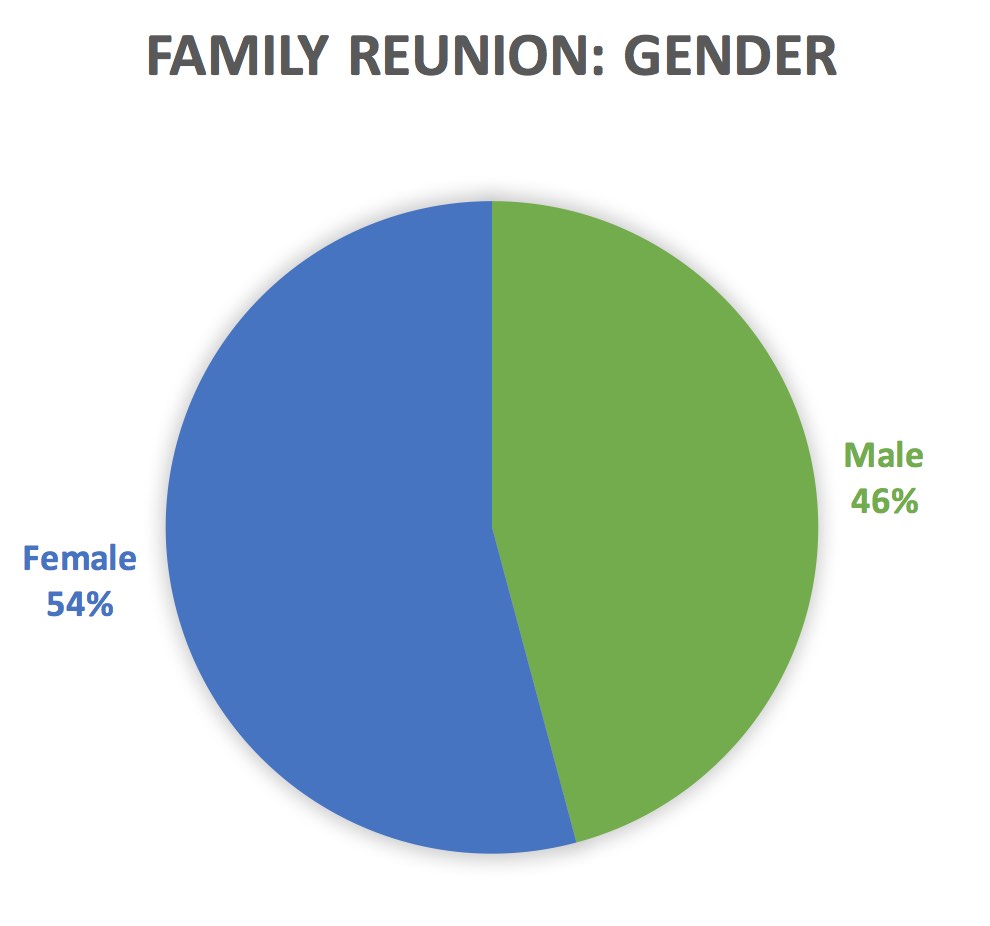

We can also use charts with pictures and classroom tasks to increase the level of rigor. Learners can work together to chart the information they see in a picture. For example, in the picture above, learners could chart the ages and gender of people at the party and use a language frame to describe their chart.

‘Based on our observations, the young adult group is the largest at the reunion.’

‘According to our calculations, there are 54% more females than males at the reunion.’

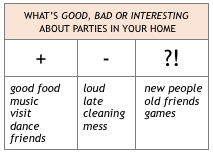

Using this same picture, learners could use a plus/minus/ interesting chart to brainstorm what’s good, bad, and or interesting about having a large group of people in your home. As learners respond, the teacher can guide them to the picture to support their “claims.”

Sample exchange

T: What’s good about having a party in your home?

S: Food.

T: What about the food?

S: People with food.

T: People bring food?

Learners could also survey teammates based on the picture topic; e.g. Do you like small parties or large parties? Once they have their data, they can chart it and share the results: Based on a survey of ___ students, we found that ____% prefer large parties to small parties.

DIRECTED DISCUSSIONS

Sentence frames (like the ones shown above) are an effective tool to help all learners practice using an academic or professional register to express their ideas. Beginners can engage in academic discourse with teacher support. First, prompt teams or the whole class to reflect on a situation within the picture, then provide sentence frames for their responses.

For example,

For example,

PROMPT: Imagine you are at the party and you see this little boy.

What do you do? What do you say?

FRAMES: In this situation, I would talk to him and say….

I would speak to his parents and say…

I would do nothing because….

Practice various responses using the frames and then direct learners to take turns expressing their ideas in teams, using the frames you’ve provided. Be sure to give learners examples of the language to agree or disagree, so that they can respond to their teammates. And don’t forget to set a time limit!

Treating visuals as complex text, giving learners opportunities to chart or graph information, and using sentence frames to practice a professional or academic register are just a few ways we can infuse rigor in beginning level instruction, demonstrating our respect for our learners’ abilities and insuring relevance in the century of complexity.

Join me for a live webinar on October 14 to further explore how visuals and scaffolded tasks can launch our beginning learners towards their educational career and civic goals.

Citations

Chui, G. (2000, January 23). ‘UNIFIED THEORY’ IS GETTING CLOSER, HAWKING PREDICTS. San Jose Mercury News, p. 29A.

Boaler, J. (n.d.). Mistakes Grow Your Brain [Web log post]. Retrieved September 24, 2016, from https://www.youcubed.org/think-it-up/mistakes-grow-brain/

Dweck, C. (n.d.). Carol Dweck on Struggle

. Retrieved September 24, 2016, from https://www.teachingchannel.org/videos/embracing-struggle-exl

Moser, J. S., Schroder, H. S., Heeter, C., Moran, T. P., & Lee, Y. H. (2011). Mind Your Errors Evidence for a Neural Mechanism Linking Growth Mind-Set to Adaptive Posterror Adjustments. Psychological Science, 0956797611419520.

[…] Visit Website […]