Jon Hird teaches English at the University of Oxford, writes ELT materials and gives teacher-training talks and workshops both in the UK and overseas. He has written and contributed to a number of ELT publications including Oxford Learner’s Pocket Verbs and Tenses.

Jon Hird teaches English at the University of Oxford, writes ELT materials and gives teacher-training talks and workshops both in the UK and overseas. He has written and contributed to a number of ELT publications including Oxford Learner’s Pocket Verbs and Tenses.

In terms of basic syntax, much of the grammar that we teach tends to be based on subject-verb-object word order. While more formal English tends to adhere to this conventional word order, the grammar of more informal and conversational spoken English can be in a number of ways quite different. For example, by putting the object, complement or adverbial at the beginning of the sentence or clause (fronting) or by putting the subject at the end (tailing), we can shift the focus and emphasis in an utterance. This also occurs in conversational written English in online social media. In this blog, we look at some common patterns of this spoken and ‘online’ grammar and, as much of it is relatively straightforward in terms of form and use, we will also consider simple awareness-raising and practice activities that can be incorporated into our teaching.

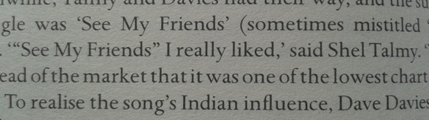

Fronting in its simplest form is when we put what conventionally comes at or towards the end of the clause (e.g. object, complement, adverbial, question-word clause) in front of it. We do this to put focus and emphasis on the object, complement etc. It can also enhance cohesion. This kind of fronting is relatively straightforward in that there are no other changes apart from the change in word order. For example, in the following extract, taken from a biography of the British band The Kinks, the song ‘See My Friends’ is fronted.

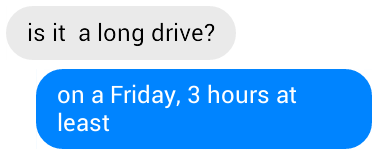

Here are some more examples of simple fronting, some of them from written online conversations.

Fifty pounds that cost me! This one I’ve had for ages. What it’s based on, I don’t know.

![]()

![]()

Another pattern of fronting (also sometimes known as using a head or header) is when we move the object to before the main clause and use a pronoun for the object as well, e.g. my keys and them in the first example below. We use fronting in this way as an orienting device to put the ‘topic’ at the beginning of the sentence.

My keys, I can’t find them anywhere. The tickets, how much were they?

That bag over there, is it yours? That book I lent you, have you read it yet?

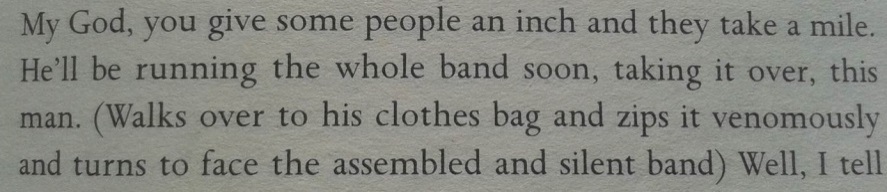

Tailing (or using a tail) is when we put the subject after the main clause and use a pronoun for this subject at the beginning of it, e.g. He …this man in the example below. Restating the full subject after the clause puts extra focus on it and emphasizes, amplifies or clarifies it.

Here are some more examples.

It’s always pretty good, the food here. He’s a great drummer, Brian Downey.

It’s a great place, Sheffield, don’t you think? She’s American, isn’t she, Suzy?

Another common pattern is It … that or this.

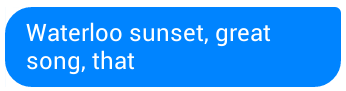

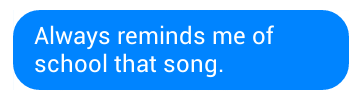

It’s a great film, that. It was fun, that. It’s a nice place, this.

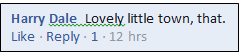

The various patterns described above are often used in conjunction with ellipsis, where unstressed words such as the pronoun, the verb be and/or the article are omitted. The examples below are all from online conversations and some are quite typical of this genre in that there is possibly a higher degree of ellipsis than would occur in spoken conversation. For example, in speaking, we are perhaps more likely to hear the ‘near ellipsis’ s’great song, that and s’lovely little town, that.

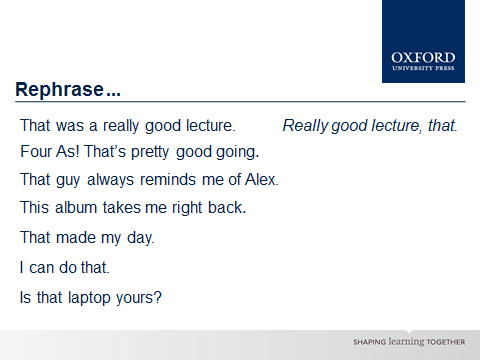

In class, one way we can look at fronting and tailing is by presenting the students with examples such as those above and asking them to notice and identify the difference in syntax compared to the more conventional word order. Such activities can focus on just one of the grammar patterns described above or a combination. Once the patterns have been established, the learners can also do simple exercises in which they rephrase sentences with more conventional word order using fronting and tailing. This could include sentences in isolation or in more contextualized short exchanges or dialogues, which can then be practised in pairs. The slide below, from a recent presentation on spoken grammar, shows an example of a simple awareness-raising/practice exercise (answers at the end of the blog).

This syntactic aspect of spoken grammar is something that learners of English are very likely to come across outside the classroom. And it seems to be a feature that some tend to pick up on and use with relative ease. So, whether we actively teach this aspect of spoken grammar or maybe just deal with it if and when it crops up, it is useful to have some straightforward explanations at the ready and a few simple examples and activities that can help illustrate, explain and practise the language.

Answers:

(It was a) Really good lecture, that. / (It was) Really good, that lecture.

Four As! (It’s) Pretty good going, that.

(He) Always reminds me of Alex, that guy.

(It) Takes me right back, that album.

(It) Made my day, that.

That, I can do.

That laptop, is it yours? / Is it yours, that laptop?

Excellent article on functional grammar! Thanks!

http://Www.ericksoneducationalconsulting.com

Thank you, Bridget. I’m glad you found it interesting.

Reblogged this on hungarywolf.

Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter.

Reblogged this on Ajarndonald's Blog.

Please i want to learn English i only go primary school. He hard me to write i need help.

Great article on spoken language structures !

Let me me know if you will hold a webinar on this subject in the near future.

Thanks.

Hi

I need to know how can I learn grammar English

Thanks

I want to continue,this excercise. How to?

Exploring spoken grammar opens up a fascinating realm of language dynamics! It’s where authenticity and fluidity shine, reflecting the vibrant tapestry of human communication. Embracing its nuances enriches our understanding and appreciation of language’s living, breathing nature.