Following Peter Astley’s introduction to the oil and gas industry, Lewis Lansford, co-author of Oil and Gas 1, considers the confusion British vs American English can cause in international industry, and whether this is countered by the emergence of ‘World English’.

Following Peter Astley’s introduction to the oil and gas industry, Lewis Lansford, co-author of Oil and Gas 1, considers the confusion British vs American English can cause in international industry, and whether this is countered by the emergence of ‘World English’.

When I began teaching in Barcelona in the late-80s, I was surprised by the intensity of the rivalry between students at the Institute of North American Studies and those at the British Council over the question of which variety of English was superior. Some teachers, too, expressed firmly held positions on the matter. But in today’s international workplace, Global English may have ended the debate by swallowing both the American and British varieties whole.

“I was the only native British English speaker on the team” says Peter Astley, remembering his stint as a project controls manager in the oil and gas industry in Kuwait. “I reported to a Texan project manager. We had an Anglo-Indian clerk and two Polish women – one setting up the computer system and the other a trainee scheduler. The engineering manager who was being transferred from another project was from Lebanon. Various high-ranking Kuwaitis floated in and out. The client I interfaced with was Indian.

“The Texan, of course, spoke English, but I often had to translate what he had said to the Indian clerk, who was also a native English speaker. The clerk disliked admitting he didn’t understand something, so I often had to decode instructions from the Texan even though I wasn’t present when the request was made.  The Texan didn’t allow the Polish girls to speak Polish in the office even though he couldn’t understand the Indian clerk’s English.”

The Texan didn’t allow the Polish girls to speak Polish in the office even though he couldn’t understand the Indian clerk’s English.”

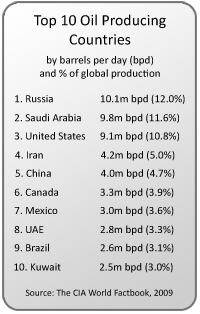

More than 100 countries produce oil. Many of the largest producers in the industry – Saudi Arabia, Russia, Kuwait, and many others – employ a diverse workforce made up of both local and imported expertise. When people from all over the world work together, English is frequently the main language of communication. But this lingua franca, often called World English, is rarely identifiable as either British or American. It generally encompasses both – and a whole lot more.

Spelling differences are the easy part: liter/litre; color/colour; sulfur/sulphur. The “other” spellings may be unfamiliar or seem wrong at first, but they’re unlikely to cause any real confusion. However, workers at all levels in the oil and gas industry have to contend with at least two basic sets of terminology for items where the possibility for confusion is real:

| BrE | AmE |

| Bitumen | Asphalt |

| Kerosene | Jet fuel |

| Paraffin oil | Kerosene |

| Petrol | Petroleum/gas |

| Spanner | Wrench |

| Wrench | Adjustable wrench |

But it’s often not even as simple as that. Geno Foushee, a native speaker of American English and intermediate Spanish speaker, works on a drilling crew in Northern Mexico – they’re looking for water, not oil, but the company that’s handling the drilling also works in the petroleum industry. “The top guys in the camp, the ones who approve contracts and invoices are Chinese. We have Canadian, American, and Mexican geologists and hydrologists. The camp hands are Mexican. They collect samples and do routine data collection, along with keeping vehicles fuelled, the camp provisioned, and so on. We’ve had Mexican drillers, an Italian driller (living in Peru), and a German-Canadian driller. We’ve got a crew using a hand-portable diamond core drill. They’re from Mexico, Peru, and Ecuador. The bigger drill rig is run by a crew of Québécois (French-speaking Quebecers). We’ve recently had a few consultants on site: an American geologist with decent Spanish, a Brit, a Colombian (living in Toronto) and a Mexico City Mexican. The cooks are Mexican.”

On the drill rig, Spanish is the lingua franca, but among people for whom English is a native language, or whose English is better than their Spanish, English the language of choice. The question of whether British or American English is used is absurd in this language environment, and in the one described by Astley. Everyone has to know that petrol and gasoline mean the same thing. Nobody’s much bothered that Americans write sulfur when Brits write sulphur. Canadians, apparently, use both. “Even among English speakers,” Foushee says, “we routinely use barreno (boring, drilling), aguaje (spring), and pozo (sump, pond, depression – typically made to hold our drill cuttings and well discharge)” – all Spanish language technical terms.

Estimates vary, but probably 400 million people in the world speak English natively. At least twice that many, and very likely a lot more, are non-native speakers. This English, in many instances, adapts itself to a vast range of work situations. This is global English. World English. The notion that there’s a conflict to be fought between British and American English may still have some currency in Barcelona, but at the well head, where the oil comes out of the ground and there’s a job to do, what really matters is clear communication. As teachers and materials writers, we should bury the language-variety hatchet, stop worrying about varietal superiority, and expose our students to as much authentic English as possible. This will give them what they need to get on with the job.

Am a Floorman with rig 188 of GWDC from china currently working in kenya geothermal fields.I have found the article very educative.can you send me more via my email? thanks in advance.

[…] The AmEng/BrEng varietal debate may not be as interesting as all that. Check out my OUP authors’ blog entry: World English at the well head. […]

[…] The confusion British vs American English can cause in international industry. […]