Students often find it difficult to engage with reading and writing instruction and practice, particularly when large, intimidating texts are involved. This is the second in our series of insight blog posts, aimed at helping teachers to overcome this problem. Here are the Top 10 Tips for Using Literature (Part 1), from teacher-trainer Edmund Dudley.

Students often find it difficult to engage with reading and writing instruction and practice, particularly when large, intimidating texts are involved. This is the second in our series of insight blog posts, aimed at helping teachers to overcome this problem. Here are the Top 10 Tips for Using Literature (Part 1), from teacher-trainer Edmund Dudley.

For many English teachers, love of the language and love of English literature go hand in hand. But is it the same for our students? Sadly, most teenage learners of English do not seem too excited about the topic of literature, associating it with dusty texts and tedious book reviews. In this article, we will look at some tips for using literature in simple and motivating ways in the EFL classroom.

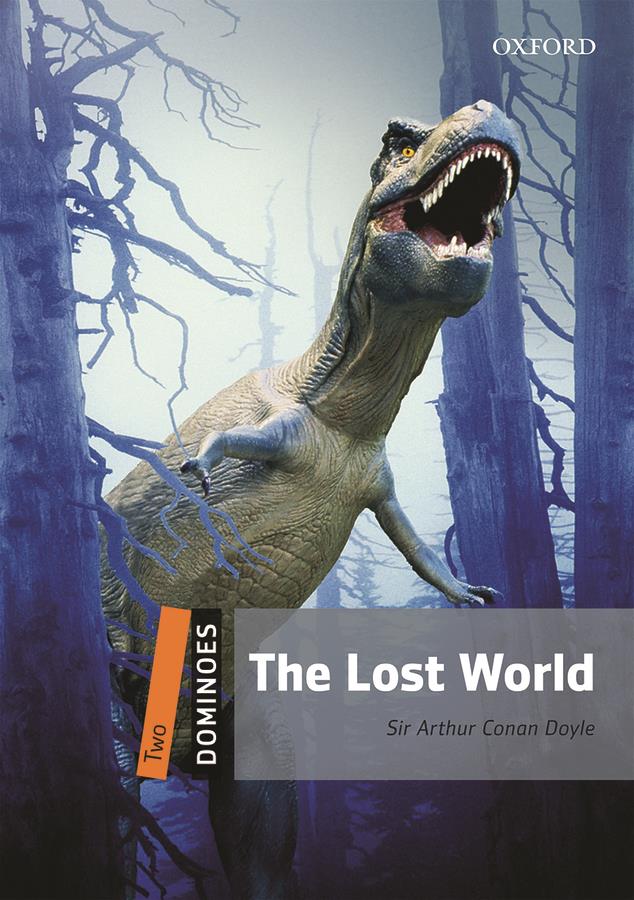

- Do judge a book by its cover!

Having a large collection of graded readers, short stories or novellas in your classroom is a great way to make literature available to your students, but in itself it does not guarantee that students will be fighting to get their hands on the titles. Many of them may not even take the trouble to look at the books. That is the first thing to tackle. Design simple quizzes that get students to make predictions about a book’s content based on the cover.

Having a large collection of graded readers, short stories or novellas in your classroom is a great way to make literature available to your students, but in itself it does not guarantee that students will be fighting to get their hands on the titles. Many of them may not even take the trouble to look at the books. That is the first thing to tackle. Design simple quizzes that get students to make predictions about a book’s content based on the cover.

Example: The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The book tells the story of a scientist who discovers that some dinosaurs are still alive and living in…

- a) Africa

- b) Asia

- c) South America

(Oxford Dominoes / Literature Insight, Insight Pre-Intermediate p.92)

In these activities, the students do not have to read anything – in fact they do not even have to open the book. You can, of course, get them to look through the book quickly to find the answer. In any case, by asking them to make a prediction we can focus their attention on the books available and, with luck, generate some interest in reading.

- Make the most of blurbs

The blurb is the text on the back cover of a book. It provides key background information and a summary of the plot. Activities that get students working with blurbs can be an effective way to continue the process of generating interest in titles and encouraging students to get the books in their hands – even if they do not actually open them up.

Again, remember that a successful classroom activity about literature does not have to involve forcing your students to read books in class. Activities such as reading blurbs and matching them to titles help the students to practise language while also tempting them to look closer at the titles available in your class library.

- Work with short extracts

Sometimes, less is more. Resist the temptation to give reluctant students long passages to read – there is actually a lot that you can do with a short extract. One simple activity is to show students a single line from a story they have not read and get them to use their imagination to make sense of the gaps in meaning. For example, you could take this line from The Railway Children:

“Tell him the things are for Peter, the boy who was sorry about the coal, then he will understand.”

The Railway Children by Edith Nesbit

(Oxford Dominoes / Literature Insight, Insight Pre-Intermediate p.90)

Who is Peter? What things does he need? Why? What happened with the coal? And who ‘will understand’? Students have not read the book, so they have no way of knowing the answers to these questions. Instead, encourage them to think creatively. In class, get students working in small groups to come up with imaginative answers to the questions. Once you have listened to all the suggestions, the students are likely to be curious about the actual answers contained in the story.

- Reading for pleasure? Make sure it’s not too difficult

Be aware of the language level when selecting a text. It is important to make sure that the texts we use are at an appropriate level and that the activities connected to the text are as engaging as possible. When it comes to reading for pleasure – also known as ‘extensive reading’ – we should make sure that the language level of the texts we use is below the level the students are actually at. That way, they will be able to read faster and also focus on the story without having to stop at regular intervals in order to look up the meaning of new words in a dictionary. By contrast, if the texts we use contain too many new words or structures then the experience of reading them stops being pleasurable and begins to resemble hard work.

- Analysing language? Make the challenge enjoyable

The activity of analysing language can be made more engaging if we use extracts from literature to introduce the features of language we would like to focus on. For example, the following short extract from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland contains two examples of antimetabole (the repetition of words in successive clauses, but in transposed order). Ask students to read the text and identify the two examples:

‘Then you must say what you mean,’ the March Hare said.

‘I do,’ Alice said quickly. ‘Well, I mean what I say. And that’s the same thing, you know.’

‘No it isn’t!’ said the Hatter. ‘Listen to this. I see what I eat means one thing, but I eat what I see means something very different.’

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

(Oxford Dominoes / Literature Insight, Insight Pre-Intermediate p.87)

Ask students to explain the difference in meaning between say what you mean and mean what you say, and between see what you eat and eat what you see. They can provide a spoken explanation, put something down in writing, or even demonstrate the difference by drawing pictures. As a follow-up, collect further examples of antimetabole on the board or on a specially made poster, complete with illustrations.

Note that although in this lesson we are focusing students’ attention on the language and how it works, by the end of the class you might find yourself with some students who are suddenly more interested in finding out more about Alice…

Edmund, those are some great insights. 😉