Successful communication entails much more than following the rules of grammar, having a large lexicon, and speaking in a way that is intelligible to the listeners. What language learners also have to attend to is how meaning is constructed in context. They have to select appropriate language forms depending on the situation and the person they are speaking with. Pragmatic competence (sometimes also called pragmatic ability) refers to using language effectively in a contextually appropriate way. People who interact with each other work jointly to co-construct and negotiate meaning depending on factors such as their respective social status, the social distance between them, the place of interaction, and their mutual rights and obligations.

Successful communication entails much more than following the rules of grammar, having a large lexicon, and speaking in a way that is intelligible to the listeners. What language learners also have to attend to is how meaning is constructed in context. They have to select appropriate language forms depending on the situation and the person they are speaking with. Pragmatic competence (sometimes also called pragmatic ability) refers to using language effectively in a contextually appropriate way. People who interact with each other work jointly to co-construct and negotiate meaning depending on factors such as their respective social status, the social distance between them, the place of interaction, and their mutual rights and obligations.

Cross-cultural and cross-linguistic differences in pragmatics

Pragmatic norms vary across languages, cultures and individuals. They are so deeply intertwined with our cultural and linguistic identities that learning pragmatics norms of another speech community, especially in adulthood, can be quite challenging. This is because culturally appropriate linguistic behaviours in the target language may differ in many ways from those in the first language (or languages). Think about the language and culture you identify with most closely (it can be your first language or another language that you use extensively in your daily life). If your language is like Russian, German or French, and makes a distinction between formal and informal ways of addressing another person (i.e., ??/??, du/sie, tu/vous), it may be difficult for you to use informal ways of addressing people of higher status such as your boss, supervisor or professor. Conversely, if your language makes no such distinction and you are learning a language that does, it may be unnatural for you to differentiate the forms of address you use depending on whether you speak to a friend or to someone of a higher social status. Languages also differ in regards to speech acts, or utterances that are intended to perform an action, such as apologies, requests, invitations, refusals, compliments and complaints. Think about compliments. How would you respond in your first or strongest language if a good friend complimented you in the following way?

Friend: “Your hair looks great! Did you just get a haircut?”

You: “…?”

A native speaker of American English is likely to say something along these lines, “Oh thanks, I just styled it differently today. I’m glad you like it.” On the other hand, a Russian may say something like, “Oh really? It’s a mess. I spent a whole hour this morning trying to style it, and that’s the best that came out of it.” It is all good if these speakers are interacting with someone of the same language background or someone who is well versed in the pragmatic norms of the same language. But put an American and a Russian together, and the interaction may end in an awkward silence because the compliment was turned down (if it’s the Russian responding to the compliment), or a bewilderment at the other person’s immodesty (if it’s the American who is responding). This and other instances of pragmatic failure can cause much more misunderstanding than grammatical or lexical errors.

Why teach pragmatics?

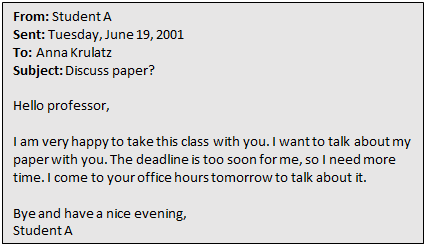

I first started to realise the importance of focusing on pragmatics in language teaching when I worked with international students at the University of Utah. Email use on campus was just beginning to gain in popularity as a medium of communication, and I would get emails from international students that came across as very informal. In fact, I started wondering if these students thought there was no difference between emailing a friend and emailing a professor. Here is a typical example:

Clearly, the goal of this message is to make a request for an extension on a deadline and a meeting during office hours. Although the email is mostly grammatically correct, it contains want- and need-statements, both of which are very direct ways of making requests. The student is also not using any hedges such as “please,” “thank you” or “would you.” Because of the context of the interaction (university campus in the United States), and the social distance between the two parties involved (student – professor), the message comes across as overly direct, bordering on impolite. As I received similar emails very frequently, I decided I had to do something to help my students develop their pragmatic competence. If your own students also struggle with the rules of netiquette, you may find this lesson plan by Thomas Mach and Shelly Ridder useful.

Unfortunately, few language courses and fewer textbooks focus explicitly on the development of pragmatic competence. Research shows, however, that language learners may not be able to notice that target language pragmatic norms are different from those in their first language, and can, therefore, benefit from pragmatics-focused activities. We looked at several examples of those in my webinar! Click here to watch the recording.

Do you have any examples of embarrassing or funny moments caused by pragmatic failure? Or ideas on how to teach pragmatics? If yes, please share your thoughts in the comments!

Anna Krulatz is Professor of English at the Faculty of Teacher Education at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim, Norway, where she works with pre- and in-service EFL teachers. Her research focuses on multilingualism with English, pragmatic development in adult language learners, content-based instruction, and language teacher education.

References

Bardovi-Harlig, K., & Mahan-Taylor, R. (2003, July). Introduction to teaching pragmatics. English Teaching Forum, 41(3), 37-39.

Rose, K. R., & Kasper, G. (2001). Pragmatics in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ishihara, N., & Cohen, A. (2010). Teaching and learning pragmatics. Where language and culture meet. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

I’ve been experimenting with drama, which seems a natural fit. I’m lucky enough to be able to use a play as content, which is language that is meant to be spoken and which illustrates human relationships with natural-sounding dialog. In the class, we might work with a scene in which one person is trying to persuade the other. We discuss their relationship and language choices. We also practice with intonation and emotional messages by taking parts and reading the script. Students then talk about similar situations in their lives. Finally, they talk about what they want to say in those situations, and I share possible ways of softening or hedging messages that might come across as harsh. Then we might role play the situations they describe. It’s a lot of fun, and students have responded well.

These sounds like great awareness-raising activities. Thank you so much for sharing your ideas! I really like the fact that you are giving your students a lot of opportunities to participate in scripted and unscripted role plays. Just curious though, how old are your students?

Recently, an adult student replied to a food picture I posted “Invite me”, because in Mexico it is common to use similar expressions when seeing an acquantaince having a delicious meal, although there is not true intention in being invited a meal. When these kinds of situations arise, I teach pragmatics through direct instruction, encouraging students to compare L1 and target language.

Hello Claudia, this is such a perfect example – thank you for sharing! I am sure this led to a very engaging discussion!

Hello, I teach English in an Italian high school. Often the students will say “Good Morning Teaching” even it’s 3 in the afternoon, They will rarely say Hello or Hi as they think it’s too informal. Good morning would to the equivalent to buon giorno which is formal and Hello and Hi would be Ciao which is considered informal. Therefore it’s necessary for me to teach “pragmatics”. Before reading this article I didn’t know the official term. Even teachers can learn and broad their horizons along with their students.

Hello Randy, thank you for your message! I am so glad to hear that you found the article relevant. If you need resources for teaching pragmatics, the US Department of State has some good ones: https://americanenglish.state.gov/resources/teaching-pragmatics. I also wholeheartedly recommend this book: N. Ishihara & A. Cohen (2012). Teaching and Learning Pragmatics. Where Language and Culture Meet. Harlow, England: Pearson.